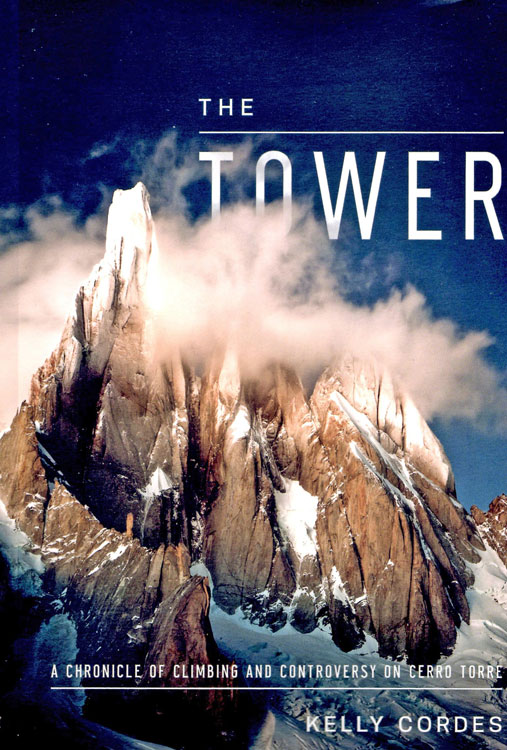

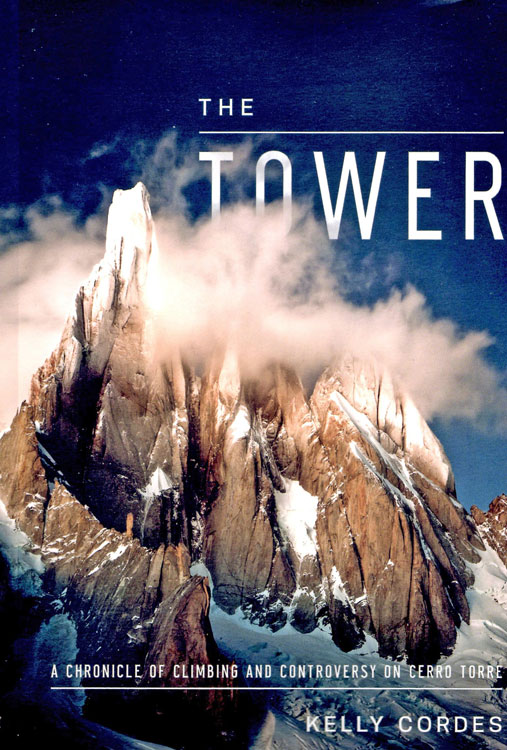

The Tower: A Chronicle of Climbing and Controversy on Cerro Torre, by Kelly Cordes, 2014

You have almost certainly seen photographs of Cerro Torre. It’s unmistakable: a narrow but very high granite tower topped by an ice formation resembling an enormous ice cream cone. But have you seen the Tower itself? I tried to in 2002, but its upper 5000 feet were concealed in cloud. This is the Tower’s normal condition. Nevertheless increasing numbers of climbers approach it every year. They may have to wait weeks for a brief weather break to try the ascent. For this is Patagonia, home of storm and wind that can actually blow you off your feet.

Mountaineering in Patagonia is recent. Its highest peak, FitzRoy, was first climbed only in 1952. And Cerro Torre? That depends on whom you believe.

In 1959 the strong Italian climber Cesare Maestri staggered off the peak, claiming that he had reached the top. His partner, the equally strong Toni Egger, had perished in an avalanche on the way down. Maestri’s account was questioned from the start. Could they have managed this extraordinarily difficult ascent in just a week, and a week of bad weather at that? There were no photographs--Egger had carried the only camera. Skepticism grew. Nobody reached the top by Maestri’s route or any other. Then, in one of the most bizarre episodes in recent climbing history, he returned to the Tower in 1970, accompanied by a 150-pound gas-powered air compressor. He and the compressor succeeded on another part of the mountain. With compressor-supplied power, Maestri drilled some 400 expansion bolts, many of them clearly unnecessary. Even then, he didn’t reach the true summit, asserting that the final ice mushroom wasn’t really part of the mountain and would some day blow away.

The summit was indisputably reached by in 1974 by an Italian party. A number of (very difficult) new routes were subsequently established; but the favorite remained Maestri’s Compressor Route. With all those bolts in place, it really wasn’t that hard. But in 2012 two young climbers made it without the aid of any of the bolts. On the way down, they removed a good many of them. The route had become hard once more. The local reaction was hostile, and the two found themselves briefly in jail.

The turbulent Cerro Torre story is far from over, but who better to present it now than Kelly Cordes? He helped edit the American Alpine Journal for many years, and he has climbed Cerro Torre. Now he has written a splendid book. The Tower is a complete history of the peak. The writing is clear and compelling. Among the book’s attractions are its photographs: many are full-page in color. An opening section of these shows the routes in all their implausible clarity. Published appropriately by Patagonia Books, this is one for your library.

In addition to being a historical account, the book is a detective story. Cordes has to confront the question: Did Maestri really climb Cerro Torre in 1959? The author is untiring in his pursuit. Like most other commentators, he answers in the negative. Maestri’s description of the route and account of the accident had a disquieting flexibility. But the most damning evidence was a lack of evidence. In 1976 a three-man party reached the summit of Torre Egger (named for Toni Egger). The first two thousand feet duplicated the route claimed by Maestri, up to the Maestri-named Col of Conquest. No one had been there since 1959. On the first thousand feet they found abundant signs of precedence, culminating in an equipment dump near a prominent snowfield. Above that, nothing: not a piton, not a bolt, no ropes, no rappel points. Maestri’s description of the difficulties below the Col were utterly inaccurate. It was very hard to believe that he had really been there. And when the section above the Col was eventually climbed, no sign of an earlier ascent was found there either.

The falsity of Maestri’s account was sufficiently established for David Roberts to include it in Great Exploration Hoaxes (1982), along with Frederick Cook’s thoroughly discredited claim to the first ascent of Denali in 1906. Maestri has poisoned his case in interviews, with vague route descriptions and a lot of anger. From a 2006 interview:

Can I ask you a specific question? How do you explain that there are no bolts on or above the Col of Conquest?

“Listen very carefully: When we attacked it in 1959, the north face of Cerro Torre was a solid mass of snow and ice. We went up it. Egger was the greatest ice climber in the world. We took advantage of this because the weather had been bad for three weeks and Cerro Torre was a sheet of ice. ... [Maestri reels off a string of obscenities.] But I don't give a [expletive] about all this. It has already been covered, goddamn it to hell! You can't understand.”

And after The Tower was published there came another revelation: a photo in a Maestri book that claimed to show Egger on Cerro Torre was taken on an entirely different peak.

The evident fakery prompts uncomfortable questions: When did Maestri decide to lie? Would he have done so had Egger survived? Even his description of his partner’s death has contradictions. Perhaps, as Maestri’s more charitable critics have suggested, he was so stunned by his own difficult descent, which included a long fall, that he really believed what he was saying. And possibly still does.

There is a resemblance to the disappearance of Mallory and Irvine on Everest in 1924. We will likely never know whether they made the top. Unlike Maestri, they did not survive to tell us. Maestri, though in his 80s and unwell, does know about Cerro Torre. But we readers will have to make our impartial guess. Cordes concludes in regretful condemnation: “They [Maestri and Cesarino Fava, who had been with him part of the way in 1959] failed themselves, they failed those who believed in them, and they betrayed the code of trust that is essential to climbing mountains.”

Return to Climbing page.

Return to travel page.

Return to home page.