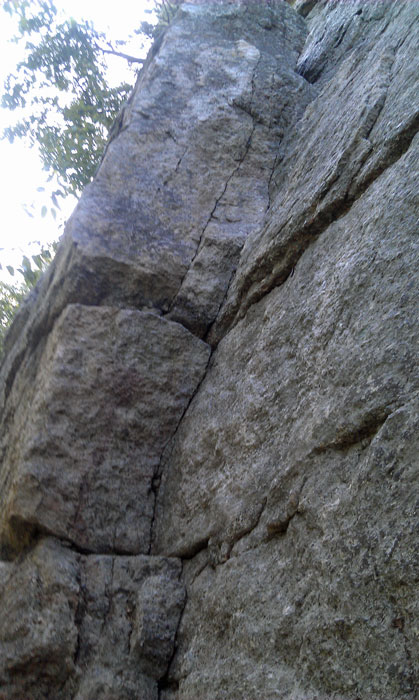

The dreaded Minty corner:My title does not refer to the enormous increase in visitors since I started climbing in 1952. Rather, I mean the change in the cliffs themselves. Newer climbers will not notice this, but it presents major problems for us old-timers. For example, Minty, known as a beginnerís route. It was the first Gunks climb I ever made, at age 14. I followed the gentle and generous George Smith, with two others. It was raining. We all wore tennis shoes, standard footwear of the day. No one had any difficulty. By the time I finished high school I had done this climb 22 more times, all on the lead. Once I did it twice the same day. It was such a trade route, one of the few I was allowed to lead under Appalachian Mountain Club rules. Sometimes I included a large 5.5 roof on the last pitch.

Twenty-two times was enough for a while, but I returned in 2002 for my 50th anniversary. Alas, Minty was temporarily out of bounds because raptors were nesting on it. I did not return for 10 years. It was then I learned of the geological changes that have affected so many routes. The trickiest move is the first: a low layback hold offset in a corner permits you to gain a huge foothold. (If you are tall you neednít bother with the layback at all: just reach up for a big, long ledge and pull.) But now that I had returned after many years I discovered that the corner had steepened. and nearly doubled in height. (This phenomenon is formally known as Gunkus crescentis horribilis.) My apprehension was aggravated by knowing that a far stronger climber than I had recently fallen, unprotected, just about here. He broke a number of bones and spent nearly a week in the hospital. I cannot recall whether this corner once hosted a piton. If so, like most protection of the old days, it was no longer there. I placed two pieces of gear--just in case, you know. The minute I grabbed the layback hold I knew I could not use it: it was too low, no doubt having sunk over the years. I stayed there a while, trying a high step that only threw me off balance. A number of kibbitzers had appeared, typical of a Saturday in the Gunks. One of them suggested a move to the right on very small footholds. I tried this a couple of times with displeasure. Nevertheless I ventured once more and managed to grasp the big albeit slightly sloping ledge. But I had no time to be triumphant: next thing I knew I was had landed on hard rock. Unlike my friend, I broke no bones: the protective gear had pulled out, yet it stopped me from going all the way to the ground. I was not hurt, merely embarrassed.

I am writing this not in a confessional spirit, but rather to alert other old-timers like me that Gunks rock has changed a lot. Donít always count on those guidebook descriptions, for you will find that many holds have grown out of reach. Another danger is that other holds, even those that have not moved, have become much smaller, some to the point of uselessness. These developments are much more serious than snakes, wasps, or climbers rappelling right on top of you.

A final note: younger climbers seem oblivious of all these changes. But they will encounter them soon enough.

--Steven Jervis, curmudgeon.

Return to Climbing page.

Return to travel page.

Return to home page.