This is not the top:My Only Rescue I was fortunate that I never had to be rescued myself. I might have been. Like most other climbers, I took risks and could have got into trouble. The closest I came was being caught by winter darkness on Mount Washington. Our lateness had already been reported to Pinkham Notch. I raced down in time to cancel the rescue mission that was in formation. Later that winter, several of my Harvard Mountaineering Club friends were lost for most of a night; one had to be hospitalized for frostbite.

In late July 1951 I participated in my only mountain rescue on Maine’s celebrated Mount Katahdin. I had just turned 14 and was briefly touring New England mountains, accompanied by Don Moser, then 22. My parents had hired Don to keep my brother and me amused and relatively quiet when they were otherwise engaged. I knew almost nothing about technical climbing, but that was more than Don knew. I wanted to ascend the prominent chimney to the east of the summit. I had heard about the route and seen photographs of the crux: a giant chockstone that had to be passed on the left. This normally required a rope. I had one but scarcely knew how to use it. Perhaps I was able to tie a bowline. Had events developed differently, Don and I might have been the ones who needed to be rescued.

Luckily for us, we deferred The Chimney for our second day in the area. On the first we scrambled up Pamola the peak’s eastern summit, taking time to look heroic on Index Rock (a giant boulder), and then traversed the knife edge to the true summit. That evening, back at Chimney Pond campsite, I looked up at our next day’s challenge. But as I was doing so, a rumor began quietly to circulate, like a ground fog: there had been an accident. In the Chimney. A young woman had been hurt in a fall, how badly was unclear. A vague call for volunteers went out. Don and I immediately started to repeat our day’s hike. By the time we had summited Pamola and dropped down to the top of The Chimney, it was dark and getting cold fast. We were the first to arrive. We had the good sense--or the fear--not to descend by ourselves to the victim. After an hour or more rescuers arrived, nearly 30 of them. Some climbed down and toward dawn emerged with a (live) body in a stretcher. We took turns handing it down the very rocky terrain to Chimney Pond. Don and I slept through much of the day.

We learned more about the accident. Marcia, about 22 years old, had been with her boyfriend David when she slipped, high up on what should have been relatively easy ground. Both were experienced and had done The Chimney three times before. They had no rope, for which they were reprimanded in the American Alpine Club’s accident reports: “It is questionable, however, whether it is wise for anyone to attempt a variation of such apparent difficulty without the protection of a rope. A rope should be considered basic equipment for all climbs on solid rock which involve any difficulty.”

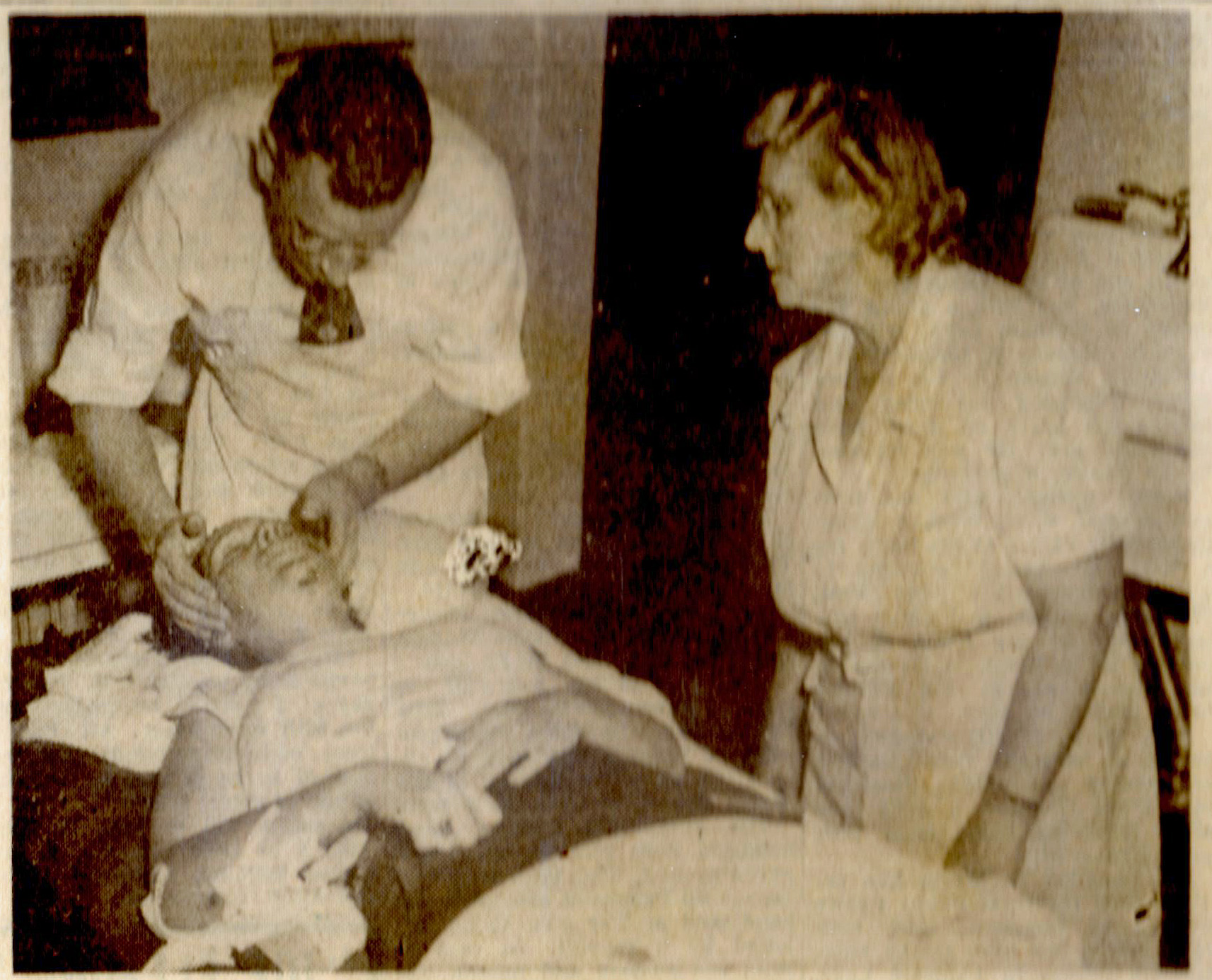

It had been a nasty fall. Marcia appeared, her face battered, on the front page of the New York em>Daily News. There was also in article in a local paper, in which I was named, but misspelled beyond recognition. The accident received extensive coverage in Appalachia (December 1951). The account urged caution, suggested that the rescued should have borne the costs of the rescue and concluded with “an old English Alpinist slogan”: “It’s not brave, but merely silly, to take a chance on getting killed.”

Marcia made a full recovery and married David. She wrote a personal letter of thanks to every one of her rescuers. I should have thanked her. Had she not fallen that day, I might have fallen the next.

Return to Climbing page.

Return to travel page.

Return to home page.